A US appeals court ruled that state-owned Turkish lender Halkbank can be prosecuted over accusations it helped Iran evade American sanctions.

The 2nd US Circuit Court of Appeals said even if the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act shielded the bank, the charge against Halkbank falls under the commercial activity exception.

Prosecutors accused Halkbank of converting oil revenue into gold and then cash to benefit Iranian interests and documenting fake food shipments to justify transfers of oil proceeds.

They also said Halkbank helped Iran secretly transfer $20 billion of restricted funds, with at least $1 billion laundered through the US financial system. (Source)

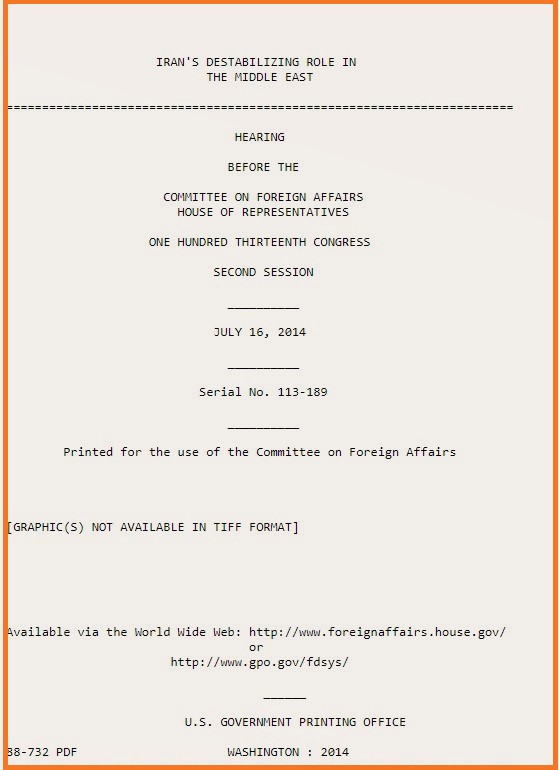

In fact, the US court’s lawsuit against Halkbank refers to financial transactions in 2012-2016, when the West imposed the first package of sanctions on Iran.

Faktyoxla Lab. has investigated if there are Armenian banks that provide uninterrupted financial services, trade deals and banking operations with Iran, as well as whether Armenia, Iran’s number one trading partner, is involved in international financial monitoring in the first and subsequent stages of sanctions.

In general, the Council of Europe’s Committee of Experts on the Evaluation of Anti-Money Laundering Measures and the Financing of Terrorism - MONEYVAL or the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development conduct annual assessments of the financial and banking systems of different countries as well as the international banking community, then why didn’t they implement an in-depth study of the monetary operations of Armenian banking and non-banking organizations?

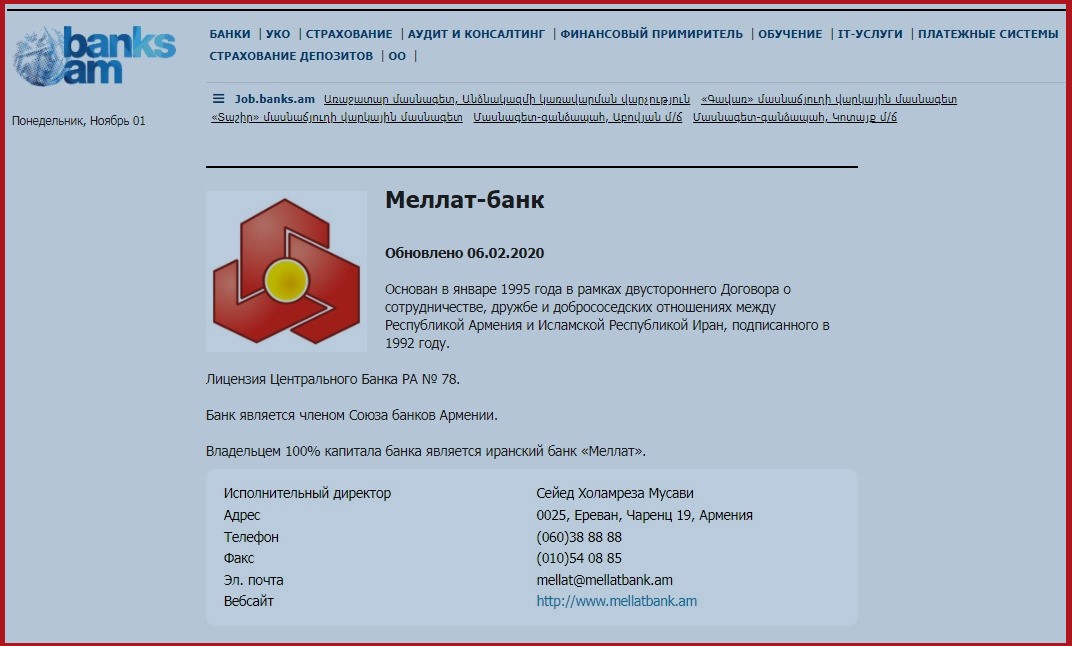

After all, Bank Mellat, one of the largest banks in Armenia, operating on the basis of Iranian capital, the authorized capital of which belongs to the religious and business community of Tehran, has been hegemonic in the country’s banking market for about 25 years. It is known that the bank, which has been operating in Armenia since 1995, is supported at the highest level by the Iranian government (Seyed Mousavi Khomeini).

We will discuss this in more detail later. First of all, let’s try to clarify what the package of sanctions against Iran includes.

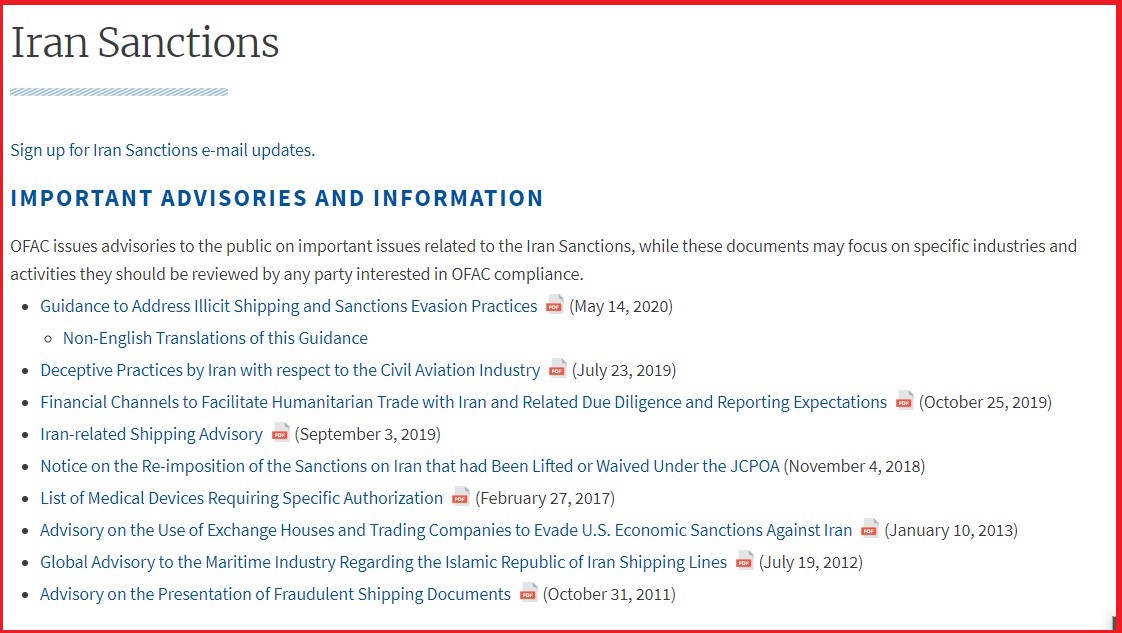

As is known, the West has adopted two sanctions packages against Iran. The first UN sanctions, imposed in 2007, included restrictions on Iran’s oil, gold and industrial products, as well as restrictions on the financial and banking sectors.

The United States and the European Union have imposed tougher sanctions on Tehran and sanctioned dozens of banks and other companies.

In 2015, Iran and the UN Security Council signed an agreement regulating and monitoring Tehran’s nuclear activities. Due to Iran’s non-compliance with the terms of the agreement, former US President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew from the agreement on May 8, 2018 and issued a statement on the resumption of sanctions against Iran. The new sanctions document, which came into force in early August 2018, provided for restrictions on Iran’s international oil exports and exports of industrial products. The European Union, which has joined the decision on various clauses, has said it will remain committed to cooperation with Iran as long as it respects its nuclear-related commitments under the updated Blocking Statute. It was stated that if Iran doesn’t comply with these commitments, the EU will take steps to restrict international trade.

The European Union joined the US decision on sanctions against Iran in early 2019, given Iran’s lack of constructive stance.

Thus, in the regime of heavy sanctions, Iran-Armenia economic relations, in contrast to economic and trade relations with many countries in the region, have expanded.

Iran and Armenia have been particularly active in financial transactions during both sanction periods. In the first phase of US sanctions, during Ahmadinejad’s rule, banks were in close contact with Armenian business groups. Reuters, one of the world’s most influential media outlets, reported in August 2012 that Iran had turned to Armenia to circumvent bank sanctions.

Iran has been trying to expand its banking activities in Armenia since 2010 to place illegal funds. Former Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan and his counterpart Mahmoud Ahmadinejad easily agreed on this. Reuters notes that at a time when international isolation is intensifying and Iran’s banking sector is being inspected around the world, its focus on Armenia raises serious questions. Armenian officials denied illicit banking links to Iran, however, Yerevan opened new financial institutions with Iran’s participation. Armenia’s ACBA-Credit Agricole Bank, which had $574 million in assets at the time, partnered with Iran.

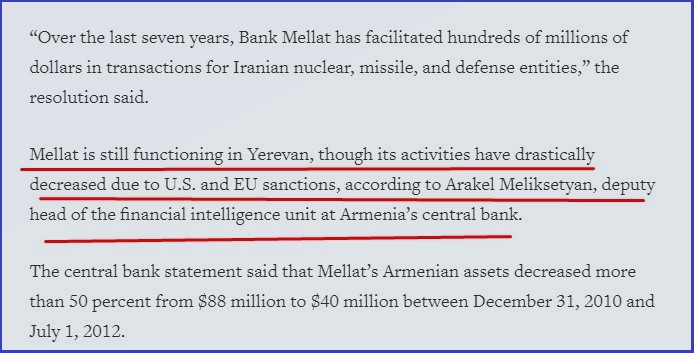

Another bank that has long concerned Western powers is the Armenian branch of Iran’s Bank Mellat, which has been under US sanctions since 2007. While Mellat is not under UN sanctions, the Security Council cited it as a problematic bank in the text of its fourth sanctions resolution, passed in June 2010. The formation of the bank’s most active financial portfolios in Armenia and Syria really sends very serious signals. It is no secret that the two countries have become a hotbed of illegal arms trade and terrorist financing, as well as money laundering. “Over the last seven years, Bank Mellat has facilitated hundreds of millions of dollars in transactions for Iranian nuclear, missile, and defense entities,” the resolution said.

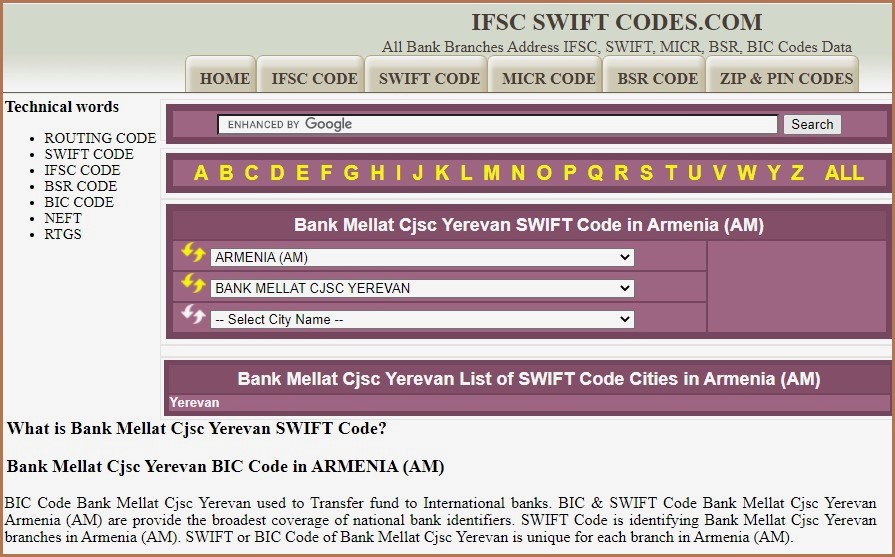

Mellat is still functioning in Yerevan, though its activities have drastically decreased due to US and EU sanctions, according to Arakel Meliksetyan, deputy head of the financial intelligence unit at Armenia’s central bank.

Mellat is cut off from the US, European and other financial markets and has virtually no business with other Armenian banks, Meliksetyan said. Since it was disconnected from the SWIFT system earlier this year, Mellat Armenia is no longer able to send or receive international wire transfers, he added. But when looking at the SWIFT payment system, it can be seen that Bank Mellat is open to all financial transactions, just like before.

Armenian media also admit that at a time when Tehran’s international isolation from the West is growing, Western intelligence reports cite ACBA Credit Agricole Bank as one of the main targets of Iran. Interestingly, in 2012, Washington openly stated to world governments that countries trading with Iranian companies sanctioned by the US could be blacklisted. Why has the Yerevan government, where ACBA Bank and Bank Mellat are located, been ignored in the face of international economic crime?

Another noteworthy point in this regard is that the corrupt Serzh Sargsyan, who concentrated the Armenian business in his hands in those years, and his close circle, Mellat Iran, willingly took part in this “thriving business.” The bank, which has invested in the Arsakh power plant, has also provided “financial assistance” to Karabakh through similar projects.

Statements of reliable sources and intelligence confirm that the bank has repeatedly transferred money to the separatist regime in Khankendi. From this point of view, there is no doubt that Mellat Iran is financing terrorism in Karabakh. The bank was involved in money laundering, terrorism and illegal arms trafficking, both in Yerevan and in the occupied Azerbaijani territories.

The products acted as food and household goods on the basis of these “business” projects managed by Iran were in fact dangerous goods of dubious origin, and the labels of these goods from Iran were changed and sold as Armenian goods in Russia and Europe under the name of industrial products. The financial intermediaries in this process were Bank Mellat and Markel CJSC. There are reports that the United States has blacklisted these organizations.

Information on Iran’s exploitation of natural resources in the occupied Azerbaijani territories and their export to the world market has been spreading for years, and the Tehran government has not denied these facts. It is no secret to anyone that gold, mercury, obsidian, onyx, facing stone, clay, pumice, agate, sawn stone, limestone for soda, molybdenum, marble, granite, lime, tuff, chalcedony, zinc, copper and other natural resources in the occupied Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding areas, as well as raw materials needed for the furniture industry, are sold through Iran and in return the so-called Nagorno-Karabakh budget is financed.

The point is that Yerevan and Tehran, with the financial support of the Armenian lobby, also directed the money sent to Karabakh to the arms business under the guise of the social life of Armenians. These operations were carried out with the direct blessing of Seyed Gholamreza Mousavi, the head of the Yerevan branch of the Bank Mellat. Hrachya Hovhannisyan, the head of the Yerevan branch, was prosecuted for “disclosing bank secrets” for the Bank’s failure to provide financial assistance to the so-called regime.

A special report by the US Treasury Department on Iran in 2004 stated that the Tehran regime spends most of its oil, gas and other economic resources on the implementation of the “Iranian Islamic Revolution” in the Middle East. In fact, behind these intentions are weapons and financial support to terrorist networks.

At all times when the Tehran regime is facing international economic sanctions, the banking sector in Yerevan is ready to help legalizing Iran’s financial sector. ACBA-Credit Agricole, Anelik Bank, Ararat Bank, ArdshinBank, ArmBusinessBank, ArmSwissBank, Byblos Bank, InecoBank, ConverseBank, Bank Mellat, PanArmenianBank, Prometey Bank, Rietumu Banka and other banks compete fiercely for the legal status of their assets subject to ‘dirty money’ and ‘embargo.’ About 100 Iranian companies operated illegally in Nagorno-Karabakh, and their financial transactions were carried out directly by Armenian banks and joint banking institutions. During the operation of Mona Group, Kankar, Suleymani, Arya Filiz Nab, Araz Muhacir Ticaret, Aftab, Arazfood, Payan-e Saderat, Firouznejat, Kaimifa, Armen, Crown, AMO Kimya, Saba Saha, Petrojam, Derakhshan, Shahsouvari, Elivoud, Tirkaran, Shadan, Sounesar, Novjavan Brothers, Shahinans, Roberto, Paknam, Trakliyan, Zakeri, Alfapetrolium, Edko and dozens of other companies (many of which are joint ventures with Armenians) in Nagorno-Karabakh, they were carrying out remittances through Armenian banks.

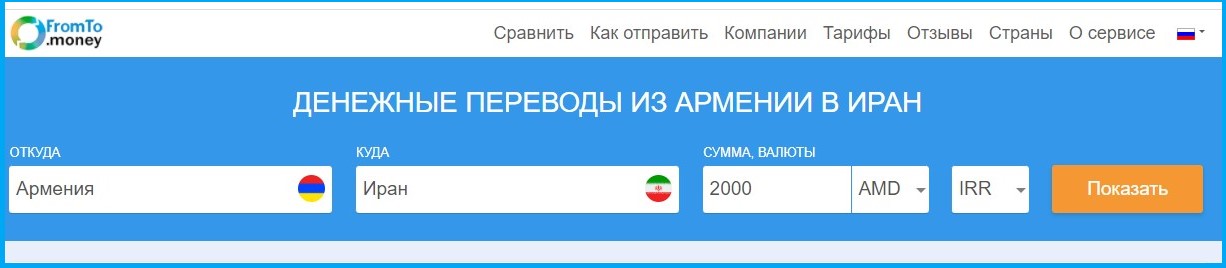

The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) announced in March 2012 that Iran would be cut off from the global interbank information system due to sanctions (the first package of sanctions is envisaged). SWIFT, an international payment system, said it was ready to comply with EU directives to close Iranian banks subject to Western financial sanctions, and warned that foreign banks joining the system were required to comply with EU rules. The reality is that Armenian banks have continued their financial transactions with Iran.

Thus, the money transferred to the banks in Khankendi was directed to the arms and drug business. Why has the West remained silent for so many years about the laundering of dirty money and the financing of arms smuggling and financial support for terrorism? After all, this is a violation of the requirements of the Montreal Convention. This means that if Azerbaijan had not liberated its territories from occupation, such international crime would have continued.

It is obvious that many banks involved in money transfers from Armenia to Iran were using payment systems. Unfortunately, the origin of the money and the purpose for which it was transferred are not investigated. It is interesting that in the absence of large Armenian businesses and financial services in Iran, there is no doubt as to the purpose for which the money was transferred. Russian payment systems are more involved in money transfers.

The fact that the Western Union international payment system is among them raises more questions. It is truly astonishing that this is happening before the eyes of the world’s financial institutions, which place the requirements of the International Convention against Money Laundering as the number one condition for all countries to ensure sound financial intermediation.

Most of the above-mentioned payment companies, despite repeated warnings from the Azerbaijani government and appeals to international organizations, have for many years carried out large-scale remittances of dubious origin, ensuring the operation of international payment systems in Khankendi.

The Central Bank of Azerbaijan has repeatedly stated the facts of payments through the MoneyGram money transfer system, which is particularly active in this process. How come the warnings of the Azerbaijani government, which stopped cooperating with MoneyGram in 2008, about the company’s dirty financial transactions weren’t heard in Europe and the US? Or how did the international financial and banking community lose sight of the fact that after the Azerbaijani government’s move to ban payment systems such as Unistream, MIGOM, LEADER, Bistraya Pochta, and Sigue Money Transfer, they launched activity in Karabakh?

Now let’s look at the relations of Armenian financial institutions with Tehran during the second package of sanctions against Iran. This round of sanctions coincides with the Pashinyan government. The point is that Nikol Pashinyan, like his predecessor Serzh Sargsyan, ignored the sanctions against Iran and continued to cooperate with Iran in banned industries.

Russia’s influential Eurasianet news agency reported in September 2019, when US sanctions against Iran were tightening, that the Pashinyan government, seeking warm relations with the US, had resorted to various tricks to ‘cut ties’ with its trade neighbor. After the visit of the then US National Security Adviser John Bolton to Yerevan, Armenian banks and financial institutions engaged in imitation for some time. Banks in Armenia continued their business with Iran as before. Bank Mellat, Inecobank and Byblos Bank Armenia have made false statements to the public that they will freeze the use of banking services. These statements remained on paper. Iranian companies were in cooperation with Armenian business circles. As a result, in 2019, Iran’s imports to Armenia increased by 30 percent. In late 2019, Nikol Pashinyan went even further, stating that Armenia does not see the need to ‘change’ its policy towards Iran. Thus, the banks, which are considered the lifeblood of trade, have become more active in this process.

It is clear that the government of Ebrahim Raisi is getting closer to Yerevan against the backdrop of Tehran’s growing anti-Western policy after the failure of initiatives to normalize relations with the United States and the European Union. Iran’s Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Yerevan Abbas Badakhshan Zohuri said at a meeting with Armenian Foreign Minister Ararat Mirzoyan that they aim to increase trade turnover to $1 billion and try to increase energy cooperation. Investments in new infrastructure were also discussed.

Conclusion: Armenia is expanding its industrial-financial-banking services with sanctioned Iran. The silence of the US Court of Appeals or other international banking community, which is seeking a lawsuit against Turkey’s Halkbank, regarding more than 10 banks and financial institutions directly involved in the Armenian-Iranian secret cooperation is quite suspicious and seems to be politically motivated.